Castration in dogs: are there really no disadvantages?

Castration in male dogs should be preceded by an individualised analysis of the potential advantages and disadvantages associated with this procedure.

Introduction

Castration in dogs is a surgical procedure performed very frequently in general clinical practice. Numerous reasons may lead to the decision to castrate a dog. The most common include the treatment of certain diseases (benign prostatic hyperplasia, perianal adenomas or testicular neoplasms) for which castration can be curative, control of unwanted reproduction and prevention of various diseases.

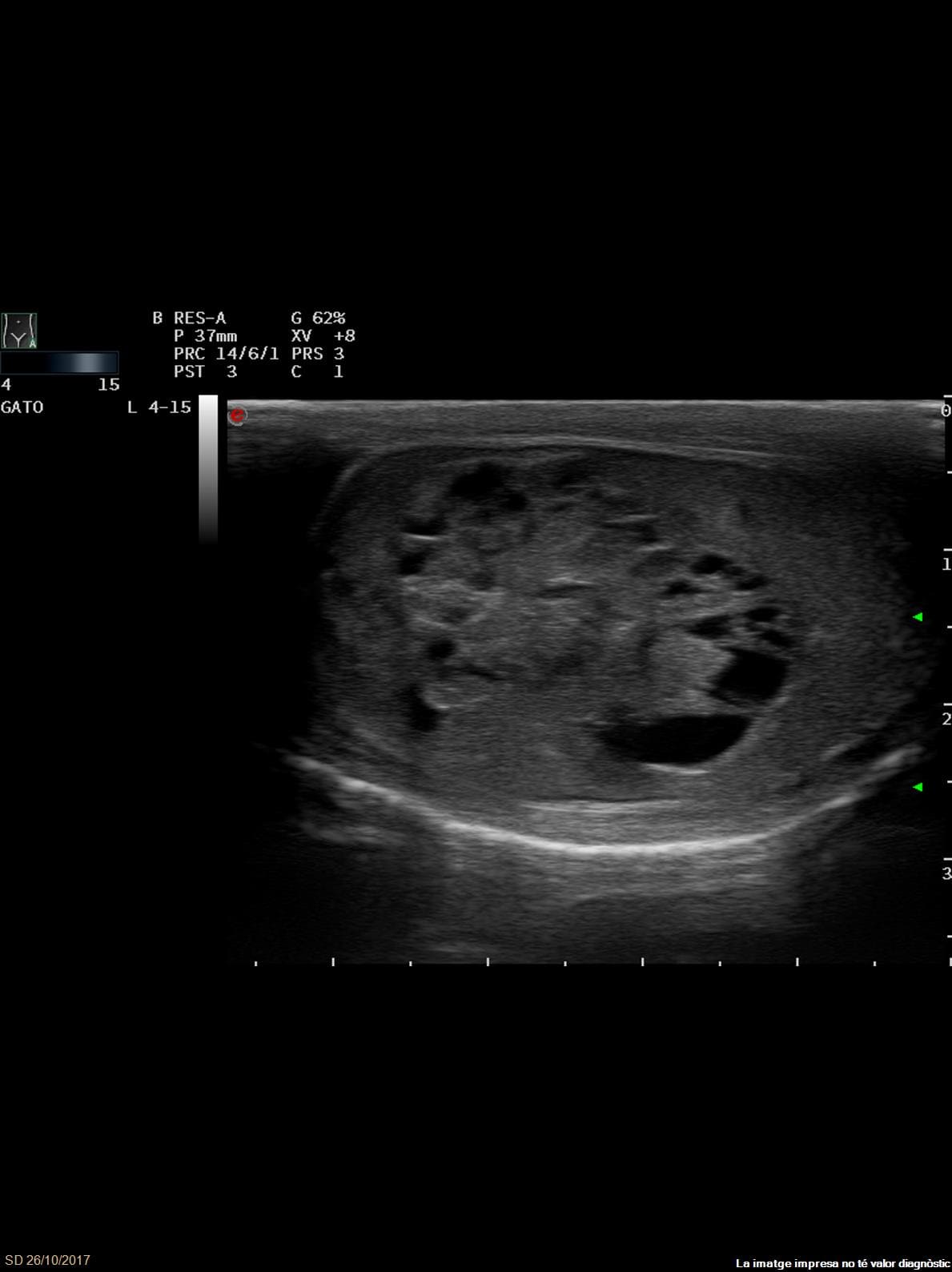

Ultrasound of a testicular tumour in a dog. A testicular nodule with poorly defined margins, containing multiple cavitated areas with anechoic content altering the normal architecture can be seen, and is diagnosed as a Leydig cell tumour.

In countries such as the United States and Australia, castration of all those dogs with no strictly reproductive purpose has been recommended for a long time, on the grounds of the need for population control and the theoretical beneficial effects of castration on long term dog health. This has led to about 80% of the canine population being castrated.1 However, there are many detractors of this practice in certain Northern European countries and Germany, and castration in dogs is actually prohibited in some of them unless there is a medical indication to support it.1,2

Furthermore, in the last 10-15 years several publications have appeared that question the benefits of “preventive” castration and suggest that castration may be associated with an increased risk of developing various diseases.

Disputes relating to castration in dogs

Debates in this regard focus on whether or not castration should be recommended in healthy dogs; its implementation as a treatment for those diseases in which it has proven to be effective is not questioned. So it is important to analyse what data we have either for or against preventive castration.

For

- One of the reasons why castration is recommended in dogs is to control canine overpopulation. In fact, the adoption of non-neutered dogs is prohibited in some countries This is one of the reasons why paediatric castration (before 16 weeks) became popular and has subsequently been a source of controversy.3 However, there are no studies showing that castration in dogs that do not roam unchecked is effective in population control.

- Castration reduces the likelihood of developing aggressive behaviours, both those linked to sexual dimorphism, and aggressiveness directed toward humans.1,2,4

- It reduces sexual behaviour and marking, although effectiveness may be influenced by the animal's prior experiences.

- It has been proposed that gonadectomy increases life expectancy in the canine population, but evidence is more robust in females than in males.4

- Castration has a direct impact on the occurrence of prostatic disease, perineal hernia and perianal tumours. It eliminates 100% of the risk of benign prostatic hyperplasia and reduces the chances of the dog developing prostatitis, abscesses and prostatic cysts.

Against

- Prostate carcinoma is more prevalent in neutered dogs than in entire dogs.

- In terms of suffering from other neoplasms:

- It seems that lymphoma and mastocytoma are more prevalent in castrated animals of the Vizsla breed.

- There is a similar finding for lymphoma in golden retrievers castrated before one year of age.

- It has also been suggested that the predisposition to hemangiosarcomas and osteosarcomas is greater in castrated males.

- Sex hormones play an important role in musculoskeletal development. This has linked castration prior to bone maturity with a greater predisposition to various orthopaedic diseases, including hip and/or elbow dysplasia and cranial cruciate ligament rupture. Although the evidence is not 100% conclusive, it seems that this effect is greater when dogs are neutered before 6 months of age.

- Other negative effects that have been associated with castration include predisposition to obesity and the development of cognitive disorders.

When to castrate and which patients to select?

Some authors have linked the age at which castration is performed with the development of various diseases. Based on this, the following has been proposed:

- Dogs whose estimated adult weight ranges between 20-39 kg should be neutered after 11 months of age.

- Castration should be postponed until 24 months in animals weighing more than 40 kg.

- Other authors suggest castrating dogs weighing less than 10 kg by 6 months of age, 10-20 kg between 6 and 8 months, 21-30 kg at 9-12 months, 31-40 kg at 10-14 months, and and finally dogs of more than 40 kg of weight at 12-24 months of age.5

In any case, it is important to remember that the fact that certain diseases are more prevalent in neutered dogs does not necessarily imply a cause-effect relationship between both processes.

Conclusions

It is difficult to make a general recommendation about whether or not to castrate a dog, and when is the right time to do this.

In the opinion of the author, the decision must be made on an individual basis and agreed with the owners after explaining the advantages and possible disadvantages that can be expected after castration. When making the decision, it is important to compare the prevalence of those diseases that are intended to be avoided with those to which the animal may be exposed as a result of castration. For example, if we consider the castration of a Yorkshire terrier to avoid prostatic disease, it is probably worthwhile to run the risk of the animal developing prostate carcinoma in the future, because prostatic hyperplasia is much more prevalent (75-80% in dogs over 6 years) than prostate carcinoma (0.3-0.6%). 3